This year’s Pecos Conference will be held in Flagstaff, Arizona.

Come Celebrate Research!

Monday, December 18th

6:00 pm

Petroglyphs, 228 S. Park Ave in the Lost Barrio

Bring a dish to share. The drinks are on us.

The AAHS Holiday Party and Research Slam is being revived and will be hosted again at Petroglyphs in the Lost Barrio just south of Broadway on Park Ave. It’s a potluck so bring a dish to share. Wine, beer and soft drinks will be provided by AAHS.

Aside from the great time and celebrating the AAHS community, why do we do this? To raise money for the AAHS Research and Travel fund!

We’ll be raising money to support original research in the Southwest with the following:

| Raffle

Tickets are $5.00 each or 5 for $20.00 and will be available at the November meeting as well as the night of the party. We’ve got some great prizes this year!

| Research Slam!

|

If you are interested in participating in the Research Slam please contact Sharlot Hart.

SANTA FE, N.M.–May 8, 2017–Attendee registration for the 2017 Pecos Conference has opened on the Attendee Registration page on our web site. We know many of you are eager to sign up for this year’s conference, taking place August 10-13, 2017 just outside Santa Fe on Rowe Mesa.

Registration for presenters and vendors is not open yet, but will be available soon.

This year there are two ways to register and to pay:

–You can register online starting at the Attendee Registration page

–Or you can register by downloading a PDF to fill out and email or mail in

To pay, you can:

–Pay online with PayPal

–Or mail in a check

This year we also have four dinner choices from Whole Hog Barbeque, a Santa Fe favorite. And, for souvenirs, we have six choices of t-shirts, 2017 logo hats and something new, 2017 logo USB drives.

All the details are on the Attendee Registration page.

Sign up as soon as possible, so we can see you in August on Rowe Mesa!

Gary Newgent

Organizer

2017 Pecos Conference

organizer@pecosconference.org

There will be no AAHS August lecture in Tucson.

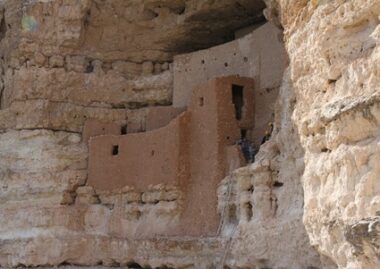

This presentation will discuss the use of archaeological information and Native American oral histories to investigate and interpret the abandonment of Castle A and Montezuma Castle, two large pueblo sites located near Camp Verde, Arizona. Archaeological data and traditional knowledge suggest that both sites were abandoned following a large and destructive fire at Castle A. Furthermore, archaeological evidence suggests this event occurred in the late 14th century and included arson and physical violence.

Native American oral histories from members of the Hopi Tribe and the Yavapai-Apache Nation recount the same violent event represented in the archaeological record. These stories suggest that a land dispute caused ancestral Yavapai and Apache people to attack Montezuma Castle and Castle A, which was inhabited by the ancestral Hopi. As the oral histories recount, the attack prompted the Castles’ inhabitants to abandon both sites and forced them on a migration path which eventually ended in the village of Songoòpavi, located on the Hopi Mesas.

Native American oral histories conflict with long-held archaeological beliefs regarding the arrival of ancestral Yavapai and Apache groups in central Arizona. While oral histories are sometimes dismissed as “inaccurate” records of the past, many archaeologists have come to increasingly rely on oral history as a way to supplement archaeological data. This presentation will illustrate how a partnership between tribal representatives and archaeologists yielded an accurate and detailed interpretation of past events at Montezuma Castle National Monument.

The arrival of settlers, soldiers, and missionaries representing the Spanish State to Alta California in 1769 fundamentally transformed Native life. Within a generation span, pueblos, presidios, ranchos, and missions were constructed up and down Alta California on lands previously inhabited and used only by Native Californians. Land previously used by Native Californians for hunting and collecting were transformed into pasture for sheep, cattle and horse or for agriculture, disrupting traditional lifeways. In short order, many Native Californians were recruited to Spanish missions and/or were incorporated into the political economy of this frontier Spanish colony.

This situation led to awkward, yet persistent, interactions between Native Californians and newly arrived Spanish settlers. Some of these sustained interactions led to relationships, which transformed into communities. This presentation looks at the nature of interaction amongst and between Native Californians and colonists during the Mission period in the Los Angeles Basin to better understand the creation and sustaining of communities. In what ways did interaction create and maintain communities? What was this interaction like, and in what settings? Using both archaeological and ethnohistoric sources, this talk creates a broad context for understanding these relationships.

LECTURE TO BE HELD IN CESL 103 Just east of the Arizona State Museum.

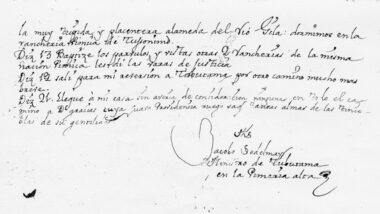

In late November, 1751, Spaniards were stunned when several hundred O’odham rose up in coordinated revolt resulting in the deaths of two Jesuit priests, some one hundred Spanish settlers, and an unknown number of O’odham. With more than fifty years elapsed since the last O’odham uprising, in 1695, Spanish officials and Jesuit missionaries had grown complacent regarding O’odham peacefulness, goodwill, and obedience, coming to rely upon O’odham cooperation as they strove to expand the Spanish colonial frontier while fending off Apache and Seri adversaries. Histories of Spanish colonization in the region seem equally unquestioning of O’odham amity during those intervening years. A close examination of contemporary Spanish written accounts, however, reveals a long and enduring tension between O’odham and European concepts of land use, social organization, and Native autonomy.

A collaborative project between the Arizona State Museum’s Office of Ethnohistorical Research and the Tohono O’odham Nation Cultural Center and Museum explores O’odham history as revealed in Spanish accounts covering two centuries of relations among O’odham and Pee Posh, Jesuits, Franciscans, Spaniards, and Mexicans. The project introduces an indigenous voice previously absent from the historical literature by including Tohono O’odham scholars and elders in reading and discussing the documents, drawing upon their cultural insights to balance and enrich interpretations of a record heavily biased in favor of European interests. This presentation offers some preliminary findings emerging from a partnership that is significantly changing how we view O’odham responses to Spanish intrusion.

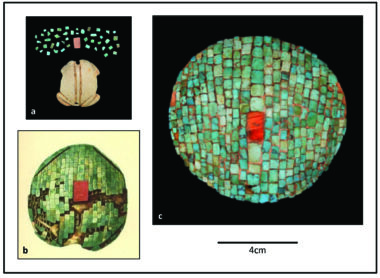

Turquoise is synonymous with the U.S. Southwest, occurring naturally in relative abundance and culturally prized for millennia. As color and material, turquoise is fundamental to the worldviews of numerous indigenous groups of the region, with notable links to moisture, sky, and personal and familial vitality. For Pueblo groups in particular, turquoise and other blue-green minerals hold a prominent place in myth, ritual, aesthetics, and cosmology. They continue to be used as important offerings, deposited in shrines and decorating objects like prayer-sticks, fetishes, and adornments. Archaeological occurrences of turquoise in contexts such as caches, structural foundations, and burials demonstrate its important, perhaps ritually oriented role in prehispanic Pueblo practices.

This presentation addresses the myriad uses of turquoise and other blue-green minerals in the late prehispanic Western Pueblo region of the U.S. Southwest (northeastern Arizona and western New Mexico, a.d. 1275–1400). Multidisciplinary research, including archaeology, geochemistry, and ethnography inform upon the role of turquoise in ancient social identification. I will outline stylistic variation in ornaments and painted items, patterns of placement in archaeological deposits (ritual offerings, for example), and regional patterns of mineral acquisition and exchange. I will be joined by Mr. Stewart B. Koyiyumptewa (Hopi Tribe) and Mr. Octavius Seowtewa (Pueblo of Zuni) to discuss contemporary Pueblo sentiments regarding turquoise, and how modern uses compare to, and in many cases clarify, archaeological patterns.