Friday, 2:00 p.m. – 5:00 p.m. AAHS Members & University of Arizona Faculty, Students, Staff

Saturday, 10:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. Open to the General Public

3:00 p.m. $5.00 a bag sale

Huge used book sale including over 1,000 books from the estate of Agnese Haury. An extraordinary collection of art, art museum catalogs, history, travel, politics, sociology and archaeology. Large number of Civil War and history books from the estate of WIlliam Longacre. Hard to find Southwest anthropology books, back issues of Kiva.

Most are under $5.00 and many $1.00. 90% of the proceeds go to support the Arizona State Museum Library.

2016 Archaeology Expo – Schedule of Events

Casa Grande Ruins National Monument

Saturday, March 5th 9 AM to 4 PM

Presentations: (Located in the Theatre):

10:00 am: “The Evolution of Ruins Conservation at Tumacacori National Historic Park: The Case Study of the Convento Compound” – Alex Lim, Tumacacori/NPS

11:30 am: “The Casa Grande Community in the Hohokam World” – Dr. Doug Craig, President/Friends of Casa Grande Ruins

1:00 pm: “Casa Grande Ruins National Monument: Significance, Intervention, and Stewardship” – R. Brooks Jeffery, Director/Drachman Institute, University of Arizona (follows with a tour of the Compound)

2:30 pm: “Southwestern Rock Calendars and Ancient Time Pieces” – Allen Dart, Executive Director/Old Pueblo Archaeology Center

On-site Tours: (Sign up at SHPO Info Booth near Exhibitors)

9:30 am: Tour of Casa Grande Ruins Compound, “Sivan Vahki O’Odham Perspective” by Barnaby Lewis, GRIC Tribal Historic Preservation Officer

9:30 am, Noon, 1:30 pm, & 2:45 pm: Tours of the Casa Grande Ruins National Monument Back Country Sites, given by Casa Grande Ruin National Monument (CGRNM) Volunteers and Southwest Archaeology Team Members (Limited to 10 people each tour)

Every Hour from 10 am to 3 pm: Tours of the Casa Grande Ruins Compound, given by CGRNM Personnel and Tribal members (if available)

2 pm: “Tour of Compound A Documentation and Assessment Project,” Laura Jensen, Gabrielle Miller, and Gabrielle Soto, University of Arizona

Offsite Tours: (Sign up at SHPO Info Booth near Exhibitors)

10:30 am: Guided Walking Tour of Florence Historic Townsite, Bonnie Bariola, Former Florence Community Development Director (limited to 30 people). Must have transportation to Florence and be able to walk between ½ to ¾ mile (meet-up information provided during sign up).

1:00 pm: Tour of Verdugo Stage Stop and Adobe One-room Schoolhouse by Dick Myers, Southwest Archaeology Team Member/Site Steward (limited to 15 people). Carpooling encouraged, rough road with no bathroom facilities, does not require 4-wheel drive, just high clearance (information provided during sign up).

Demonstrations:

Demonstrations at the exhibit booths include traditionally prepared native foods from the Huhugam Ki Museum, cotton spinning, spilt twig figurines, pump drill, puzzles, looking at pollen with a microscope, artifact analysis, and many other activities.

We are also privileged to have some additional demonstrations that we are highlighting in different areas of the Park. These demonstrations are scheduled throughout the day and include the following activities:

9:00 – 11:00 am: Flintknapping – Courtyard inside Museum – Shelby Manney, Department of Emergency & Military Affairs

11:00 am – 12:00 pm: Adobe making – Interpretive Ramada – Alex Lim, NPS

1:00 pm – 3:00 pm: Pottery making –Courtyard inside Museum – Roger Dorr, NPS

All Day: Rabbit Stick Toss (interactive activity) – In the compound – Southwest Archaeology Team Members

The Arizona Archaeological and Historical Society (AAHS) is pleased to announce a new competitive subvention award program for AAHS members. The purpose of this program is to provide money in support of the publication of digital or print books or Kiva journal articles that further AAHS’s mission. Many sources of grant funding do not support publication costs. Through this program, AAHS can provide occasional funding to prevent this barrier to the sharing of research results. In 2015, awards up to $5000 will be considered.

Award criteria:

The AAHS Publications Committee will review applications submitted by authors or editors. Applications are eligible for review after the manuscript has been accepted for publication by a press or the journal editor “as is” or “with revisions.”

The application will include a cover letter that describes the purpose of the subvention, the audience for the book or article, how publication of the manuscript is in keeping with the AAHS’s mission, and the availability of other sources of funding for publication. Supporting materials should include an abstract for the book or article, a copy of the Table of Contents (if relevant), and a copy of the letter from the press or journal editor indicating their terms for accepting the manuscript. Incomplete applications will not be considered.

The monetary award will not be paid until book or article has been finally accepted by the press or journal editor, and will be paid directly to the publisher.

The financial support of AAHS will be noted in the volume/article acknowledgments and on the copyright page of book publications.

The deadline for receipt of submissions is October 16, 2015 for consideration by the end of November.

To join AAHS go to our membership page.

Applications should be emailed to Sarah Herr .

From 1984 to 1987, William D. Hohmann, AAHS President, directed AAHS excavations at the Redtail Site (AA:12:149[ASM]) in the Northern Tucson Basin. The excavations focused on the central portion of the surface artifact scatter at the site. Four pithouses, several secondary cremations and one primary cremation as well as a variety other cultural features were excavated. This initial fieldwork demonstrated that a valuable Hohokam Colonial period occupation existed at the site. Subsequently, The Institute for American Research conducted additional work at Redtail. (Archaeological Investigations at the Redtail Site, AA:12:149 (ASM), in the Northern Tucson Basin, Mary Bernard-Shaw, Center for Desert Archaeology, Technical Report No. 89-8, 1989.)

A unique aspect of Redtail is the amount of turquoise recovered during excavations. It appears that the site has the earliest concentration of turquoise yet found in the southwest.

The artifacts from the AAHS excavations at Redtail were turned over to The Arizona State Museum (ASM) where, with the exception of the turquoise and human remains, they remained in their original field bags. In 2010 a group of AAHS volunteers rebagged and reboxed all of the artifacts and entered them into the ASM database. The original field notes, obtained from Hohmann, were scanned. The results of this voluntary effort resulted in 106 boxes of artifacts and 6 boxes of catalog material that are now available for research.

**At this time there is a hold on accepting donations. If you are able to wait until later, feel free to check back regularly. If you need to dispose of the books promptly, please check other donation locations such as your local libraries, Friends of the Pima County Library, or World Care.**

Thank you for your interest in donating books to the AAHS/ASM Library booksale. We accept a variety of generas, including archaeological reports, children’s books, novels, et cetera

- We do not accept anything in a language other than English.

- We do not accept textbooks and discourage dissertations and theses.

- We do not accept conference material (such as programs and abstract compilations).

We do not accept these Periodicals:

American Anthropologist

American Ethnologist

Current Anthropology

Historical Archaeology

Journal of Archaeological Research

Journal of Field Archaeology

SAA Archaeological Record

SMRC Revista

Periodicals we are particularly interested in are:

Arizona Highways

American Indian Art Magazine

American Antiquity

Other Periodicals are also accepted

The way donations work is that the donation itself will be to AAHS. The ASM Library will then have first pick of the donations to help fill their collection. Anything the library does not need will then be sold at a booksale sponsored by AAHS. 90% of the proceeds go to the ASM Library while 10% goes to AAHS.

There are two large booksales, one that takes place at the Southwest Indian Art Fair (SWIAF) in the spring and then one in the fall. There are also smaller sales at many of AAHS’s monthly lectures.

If you are interested in donating or volunteering to prep for or during the booksales, contact Melanie Deer at melaniedeer@email.arizona.edu or 520-626-9109.

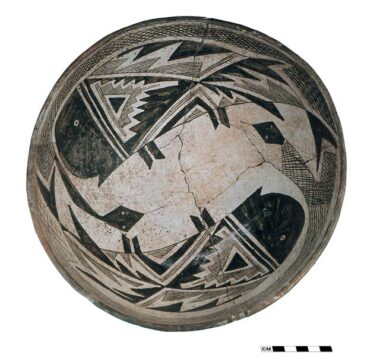

The Archaeology of the Human Experience (AHE) is a new initiative concerned with understanding what it was actually like to live in the past that archaeologists study (Hegmon 2013, 2016). This talk will have three parts. (1) I will summarize several examples of work done in this paradigm, which focus on documenting the conditions of life and human well-being in the past. In one case, people in the ancient Southwest were able recreate their society, moving from difficult and violent times to more prosperous and peaceful times. (2) I will discuss ideas for participatory archaeology that gives people – including students and the interested public – a better understanding of life in the past. Importantly, this kind of work is integral to the AHE paradigm. For example, by documenting the thermal properties of dwellings, we can understand the relative advantages and disadvantages of different kinds of settlements and consider the idea that the beautiful cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde were actually refuges from conflict. (3) I will discuss future directions, including an archaeology of creativity regarding the paintings on Mimbres pottery.

![Advertisement card for ProtexU “Lazy Dazy” vaginal ointment (© American Medical Association [1928], All rights reserved/Courtesey of AMA Archives)](https://aahs1916.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/PDI_0079-257x400.jpg)

What was it to be ill in the past for women? How did women historically respond to illness or the risk of an illness?

Historical archaeologists often find an array of objects related to medical treatment; doctor proscribed or self administered. Recovered from two late 19th and early 20th century downtown Tucson neighborhoods/archaeological sites (the Joint Courts Complex Archaeological Project and the Plaza Centro, Historic Block 91 Project) examining such material culture as douching paraphernalia presents a unique insight into women’s lived experiences of health and illness. Drawing upon historical medical scholarship and print media, women’s choices to douche were shaped by the interaction between social and medical discourse.

While douching is widely understood to have been a popular contraceptive before the advent of the birth control pill, under-discussed is its role in women’s daily lives as a multi-purpose therapeutic. Douching was part of a tradition of self-help in America reacting to not only harsh allopathic treatments but people’s desire to have choice in their treatment. Occurring simultaneously was the understanding by many orthodox and irregular doctors its utility in treating a variety of pelvic ailments under the miasmic notion of disease (i.e. imbalance and over-accumulation of toxic bodily waste) as well as limiting conception. As germ theory took hold, douching found a place in orthodox gynecology as a means for antiseptic patient preparation prior to pelvic examination and treatments from keeping wounds clean related to childbirth and pelvic disorders like endometritis. By the turn of the 20th century, a growing commercialized self-help tradition expanding into a modern health consumer culture targeted women as a group at risk. Douching advertisements at this time followed the concern that personal hygiene was paramount to reducing bacteriological disease thereby offering women autonomy in “protective cleanliness.” As we will see, women like those in Progressive Era to the Interwar Period Tucson were participating in a wider narrative in managing their bodies from birth control, infection, inflammation, and menstrual disorders to general hygiene.

In this presentation I will tell of how ancient hunters first came to the Flagstaff area toward the end of the last Ice Age, then I will describe a much later time when descendants of these hunters began to farm and live in pit house and pueblo villages. My discussion focuses on the unique nature of the Flagstaff environment and the reasons why this area is considered by the modern Hopi to be Pasiwvi (“The Place of Deliberations”). It is here, at the foot of the San Francisco Peaks, that the outlines of a more modern Hopi way of life began to take shape. Some Hopis believe that the modern Hopi ethos was first proposed and debated in kivas associated with pueblo communities here. Some pinpoint Elden Pueblo as the exact place where these things happened, others see events unfolding in multiple communities over time. In any case, the Flagstaff area is essentially a Hopi “holy land” – a place that is filled with sacred meaning and deep history.

In the Flagstaff area, two very different kind of mountains dominate the contemporary landscape and its human history: Sunset Crater and The San Francisco Peaks.

The San Francisco Peaks are a transcendent earthly feature and the sacred spiritual home of the Hopi Katsinam, spiritual guides and helpers of vital importance to the world. The Peaks have been significant to local native people for hundreds of years, if not thousands. The Peaks are at the heart of the Hopi cultural landscape, and it seems no accident that Hopis would consider this beautiful and awe-inspiring mountain to lie at the heart of their cultural history.

Sunset Crater, the other vitally important landform in the area, is very different from the San Francisco Peaks. A low and rounded pile of volcanic cinders, Sunset Crater would seem to be indistinguishable from several hundred other volcanos in the area. But like the peaks, Sunset Crater is considerably more than just another physical landform. Sunset Crater dramatically changed the world of ancient Flagstaff residents, erupting sometime in the late 1000s and leaving behind about two billion tons of lava, scoria, and cinders. When its eruption was complete, the landscape was permanently altered, destroying much of the local area, but bringing new possibilities in the form of a cinder mulch that enhanced farming.

Much of the late prehistory of the Flagstaff area is uniquely fascinating, and still rather confusing. Here, the great cultural spheres of Chaco and Hohokam overlapped. Local residents seem to have borrowed from both of those traditions, incorporating elements such as ballcourts, great-house like pueblos, and possibly even great kivas into the fabric of their existence. People also established elaborate long-distance exchange networks, leading many to consider the ancient people of the Flagstaff area as among the most accomplished traders in the entire Southwest. Residents here built large communities with impressive architectural constructions, and sustained a regional farming population that is astounding in such an austere and unpredictable environment. Yet, for all the successes that unfolded over a period of several centuries, it ultimately did not last. Beginning in the early 1200s, and unfolding over the next century or so, people left behind their homes in the land of the Peaks, and enacted their history in other places, including the Verde Valley and the Hopi Mesas.

For many centuries, the pueblo people of Flagstaff had their feet planted firmly in the earth that they farmed, but their social connections reached far across the real world and their ideas soared well into the cosmos. Flagstaff was, and is, a place of harsh physical realities but also a place of great beauty and meaning, especially to the Hopi. Few other places in the Southwest have such an enduring connection between remarkable places of the past, and resilient, enduring native people who never strayed far from their original homeland.

The most important crops that that fed the ancient peoples of the prehispanic Southwest U.S./northwest Mexico (SW/NW) came from Mesoamerica. The three sister–maize, beans, and squash—and less prominent crops moved at different rates from their homeland to the south into the SW/NW. The most important Mesoamerican crops, with one exception (OK, maybe two), that could have been grown in the SW/NW ultimately arrived here. Although not grown in the SW/NM, even cacao’s presence in the SW/NW further reinforces the view that there were few impediments to the flow of crops and foods between Mesoamerica and the SW/NW.

The one exception is the cultivated chile, Capsicum annuum. While widespread in Mesoamerica, ancient chile remains are absent the SW/NW. Adding further to the mystery of their historical absence is the fact that chile became an icon of the SW/NM food, became an important ingredient in SW/NW cuisine beginning with the Spanish arrival, and today are an important regional crop in the SW/NW.

Why didn’t chile travel a few hundred miles north when it spread widely and very quickly into the Old World after European contact with the New World? After all, what would Hungarian, Chinese, Thai, and various African cuisines be without chile?

The fortuitous discovery of the first cultivate chile from an archaeological site a few kilometers from Paquimé/Casas Grandes just across the border in northern Chihuahua provides an opportunity to reconsider dynamic history of chile and a time to challenge our common assumptions about chile.

Oh yeah, the second common Mesoamerican plant not present in the ancient SW/NW is the tomato.