- Tag

Led by Laurene Montero, Phoenix City Archaeologist and Jerry Howard, Director, Mesa Grande Archaeological Project

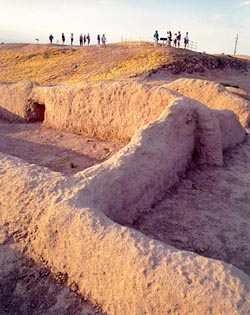

Pueblo Grande features a large platform mound with retaining walls, which was once surmounted by walled structures. There were also many houses and at least three ball courts, probably constructed starting 750 CE. We’ll also visit irrigation canals at the Park of Four Waters. After a picnic lunch, we’ll visit Mesa Grande Cultural Park, which showcases a platform mound, built between AD 1100 and 1450. The mound was the public and ceremonial center for a one of the largest Hohokam villages in the Salt River Valley, a residential area that extended for over one mile along the terrace overlooking the river.

Trip is limited to 20 people. To sign up contact Lynn Ratener.

A place of special significance to the late Preclassic Hokokam is located at the base of the western slope of the Santa Catalina Mountains near Tucson. Taken in context with other anthropological information, it appears that Sutherland Wash Rock Art District was a ceremonial place with emphasis on the Uto-Aztecan Flower World. Flowers hold special meaning to speakers of Uto-Aztecan languages representing a spiritual landscape, a flowery, colorful, glittering paradise, that can be evoked through prayers, songs and other human actions. Previously reported in kiva murals and ceramics, Jane H. Hill suggested that such imagery might also be found in rock art.

A rich set of data recently created by a team of volunteers from AAHS and the Arizona Site Stewards includes a detailed recording of 3,251 prehistoric petroglyphs, a variety of surface features, artifacts, trails, solar markers and the results of a rudimentary acoustic experiment. In these data we found three important lines of evidence suggesting the special significance of Sutherland Wash. The first is the Flower World complex which is evident not only in petroglyphs representing both realistic and abstract flowers but also in glyphs depicting important related imagery including birds and butterflies. Second, the importance of gender is apparent in many male and female anthropomorphs, vulva forms, family groups, birthing scenes, and a landscape that includes yoni and phallus formations. Third, the interaction of sunlight and shadows with some of the panels clearly marked the equinoxes and solstices; one panel is a compelling horizon marker at the summer solstice involving Romo Peak where copper bells of Mesoamerican origin were found in the 1940s.

The City of Tucson recently acquired the Adkins property at the southwestern corner of N. Craycroft Road and E. Fort Lowell Road. Used as a steel tank manufacturing location for 70 years, portions of the site were contaminated by oil and metals. As part of the clean-up efforts organized by the City of Tucson, Desert Archaeology, Inc. monitored the removal of contaminated soils. Beneath a thin layer of soil, archaeologists discovered a large number of features. These included 10 pit structures, ranging in date from A.D. 950 to shortly after A.D. 1150. Seven were completely excavated, revealing exception preservation and abundant floor artifacts. Fort-era features included a garden area, Cottonwood Row, the fort Bakery, and a corner of the Guard House. These findings provide new insights into the prehistoric Hardy Site and will guide the planned construction and interpretation of the Fort Lowell Cultural Park.

Click for LECTURE VIDEO

From approximately A.D. 1200 to 1450, and perhaps even later, University Indian Ruin was a prominent Hohokam center with platform mounds. As the only Classic period center with such public buildings in the eastern Tucson Basin, this settlement undoubtedly served as the focal point for a much larger surrounding community of interrelated small hamlets and villages. Occupied from early through late Classic phases, the site encompassed residential and ritual architecture and artifact assemblages that span this dynamic interval. After a former student donated a portion of University Indian Ruin to the Department of Archaeology in 1930, a variety of archaeologists excavated in its well-preserved core, but only Julian Hayden’s (1956) work on and around the main platform mound has been comprehensively reported.

Beginning in 2010, Paul Fish and Suzanne Fish have taught the School of Anthropology’s spring archaeological field school at University Indian Ruin in collaboration with the Arizona State Museum and Desert Archaeology, Inc. Mark Elson has co-taught the field school for two years and Jim Watson for one year, with Lawrence Conyers, Douglas Craig, and Patrick Lyons as additional research principals. Results to date help evaluate the potential to integrate previous investigation with current and future research. Methods include detailed mapping, applications of ground penetrating radar, controlled surface collections, shallow wall trenching to define architectural outlines, and excavation of selected rooms. The confirmation of a second small platform mound with attached exterior rooms and the diversity of residential structures heighten an appreciation of architectural complexity during a time of population movement, aggregation, and accelerated cultural change. Differential acquisition of polychrome types, distant obsidian, exotic chert, consumption of bison, and late prehispanic pottery of Zuni and probable Sonoran origin provide new insight into Classic period regional interaction.

Utilized for centuries by many cultures, the National Register Sears Point Archaeological District (SPAD) is located along the rich riparian habitat of the Gila River. Currently managed by the Yuma District of the Bureau of Land Management, a large portion of the District is designated an Area of Critical Environmental Concern and is still utilized by several of the 15 Tribes that claim cultural affiliation there.

Responding to a BLM request for comprehensive rock art recording, Rupestrian CyberServices and Plateau Mountain Desert Research not only mapped approximately 2000 petroglyph panels and 100 features including rock piles, rock rings, artifact scatters, a rock shelter, several apparent natural and constructed hunting blinds, geoglyphs, and scattered rock alignments; but also, many historic features and an extensive network of pre-historic, historic, and animal trails. Recording and photographing SPAD required a three-year effort with the help of 50 volunteers, and some unusual techniques.

Tucson Balloon Rides assisted us by providing a low-elevation flight path from which we observed and photographed subtle features that were otherwise difficult to view from the ground and impossible to discern from available aerial photography.

Extensive measurements were made and recorded on multiple page forms during 16 weeks of fieldwork and subsequently entered into FileMaker Pro and Excel databases. 18,000 photographs are catalogued and identified by panel number in a Portfolio image database.

This presentation will provide not only a birds-eye view of the area, but also some intriguing petroglyph designs and preliminary analyses of the 8000 individual rock art elements.

Ancient bags are depicted in Southwestern rock art and have been recovered from many archaeological sites in the region. Despite their widespread presence in the prehispanic Southwest, little research has been conducted on their styles, archaeological contexts, and uses. Ethnographic research suggests they served as medicine bags, as containers for tool kits and foodstuffs, or simply to haul things around. In indigenous Mexico and Guatemala, woven bags are traditionally a man’s accessory and often a male product. What is the evidence for their use and production in the U.S. Southwest?

In this presentation, a rock-art researcher and an archaeological perishables specialist team up to explore a variety of questions related to bags. How are they depicted in rock art? What forms are portrayed? In what contexts do they occur? What kinds of archaeological examples survive in museum collections, how were they made, and what did they contain? Taken together, what do these multiple lines of evidence suggest about the uses of bags in the ancient Southwest?

Drawing from rock art images from the San Juan River corridor of southeastern Utah, depictions from other regions, the Southwestern archaeological literature, and ethnographic information from other parts of the world, we embark on a visual and cultural exploration of this rarely considered, but always ubiquitous, item of material culture.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Arizona Archaeological and Historical Society volunteers, University of Arizona students, and Pima College students excavated Whiptail Ruin, a village in the northeastern Tucson Basin that dates to the mid- to late A.D. 1200s. Analyses of the notes and artifacts from the site are now finished, with some interesting results.

Whiptail Ruin, situated in and around Agua Caliente Park and its hot springs, contains evidence that some of its residents were part of a thirteenth-century migration from the Mogollon highlands. Locally made corrugated pottery, Cibola White ware jars used as cremation urns, obsidian from the Mule Creek source near the Arizona-New Mexico border, and the use of tree-ring datable conifer wood in house building are indicators of strong ties with people outside of the Tucson Basin.

Other evidence suggests that Whiptail’s residents may have been specialized hunters. Skulls, jaws, horns, antlers, and lower leg bones of deer, pronghorn, and bighorn sheep appear to have been stored on shelves or on the roofs of houses. If the Hohokam were doing what historic O’odham hunters did, some of these items may have been parts of hunting costumes, while others were pieces stored away to protect the other villagers from the power of the animals that were killed.

In April’s talk, Linda Gregonis will discuss the possible role of hunting specialists and migrant families in the early Classic period as well as describing the challenges of working with data recovered and field notes made nearly 40 years ago by avocationalists and archaeological students.

Join us for a van tour led by

Join us for a van tour led by- Demion Clinco, President of

- the Tucson Historic Preservation

- Society. We will see what

- remains of 1950’s tourist Tucson.

- Neon lights, tourist courts,

- old gas stations. There is a $10

- charge and non-AAHS members

- are welcome. To register contact

- Katherine Cerino.

The Cebolla Creek area of west-central New Mexico is an isolated area of lava flows, pinyon-juniper forests, and flat valley bottoms that is part of the El Malpais National Conservation Area. Completely depopulated today, in the early 20th century the area was home to Navajo, Hispanic, and Anglo populations who hunted, gathered, and farmed the canyon’s resources. Research over the past five years has illuminated aspects of interaction and land-use by these groups during a critical time in New Mexico’s history.

In particular, this presentation discusses heretofore unknown early 20th century Navajo sites and the Sue Savage Homestead (LA 74544), a complex of more than 25 structures and features occupied by a widow and her children during the Great Depression. This presentation uses tree-ring data, historical documents, and oral histories to illuminate the hardscrabble life of the area’s occupants and place the occupations in their proper environmental and social contexts. This research has lessons for archaeologists estimating length of occupations and for comparing different data types.

The discovery of cacao residues in ceramics from Chaco Canyon raises questions about how and when populations in the American Southwest acquired chocolate, how it was obtained from the tropical areas where cacao grows, and how populations in the American Southwest incorporated cacao into their lives. Ongoing research into the temporal and spatial distribution of cacao in the Southwest is highlighted, along with what this means for interaction with Mesoamerican populations.

While scholars have long known that southwestern populations exchanged goods with populations in Mesoamerica, our knowledge of the extent and nature of this exchange is changing as new information about cacao consumption in the American Southwest comes to light. As new information about cacao use comes to light, archaeologists are reinterpreting connections with Mesoamerica and the types of ritual activities conducted in the American Southwest.

The Spanish took control of cacao production, exchange and use soon after their arrival in Mesoamerica, and cacao consumption is not noted among the early chronicles of southwestern explorers. Yet, Spanish settlers, soldiers and priests soon reintroduced cacao into the Southwest, and it became an important commodity for interaction between the Spanish and Native American groups. Archaeological evidence and historical documents confirm the continuing allure of cacao within the scope of southwestern history.