- Tag

From approximately A.D. 1200 to 1450, and perhaps even later, University Indian Ruin was a prominent Hohokam center with platform mounds. As the only Classic period center with such public buildings in the eastern Tucson Basin, this settlement undoubtedly served as the focal point for a much larger surrounding community of interrelated small hamlets and villages. Occupied from early through late Classic phases, the site encompassed residential and ritual architecture and artifact assemblages that span this dynamic interval. After a former student donated a portion of University Indian Ruin to the Department of Archaeology in 1930, a variety of archaeologists excavated in its well-preserved core, but only Julian Hayden’s (1956) work on and around the main platform mound has been comprehensively reported.

Beginning in 2010, Paul Fish and Suzanne Fish have taught the School of Anthropology’s spring archaeological field school at University Indian Ruin in collaboration with the Arizona State Museum and Desert Archaeology, Inc. Mark Elson has co-taught the field school for two years and Jim Watson for one year, with Lawrence Conyers, Douglas Craig, and Patrick Lyons as additional research principals. Results to date help evaluate the potential to integrate previous investigation with current and future research. Methods include detailed mapping, applications of ground penetrating radar, controlled surface collections, shallow wall trenching to define architectural outlines, and excavation of selected rooms. The confirmation of a second small platform mound with attached exterior rooms and the diversity of residential structures heighten an appreciation of architectural complexity during a time of population movement, aggregation, and accelerated cultural change. Differential acquisition of polychrome types, distant obsidian, exotic chert, consumption of bison, and late prehispanic pottery of Zuni and probable Sonoran origin provide new insight into Classic period regional interaction.

WAITING LIST ONLY

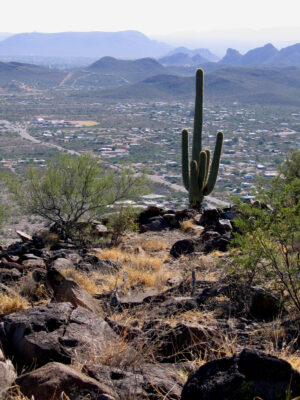

Tumamoc Hill just west of the Santa Cruz river in downtown Tucson is a trincheras site with occupations going back to 500 BC. There are also a large number of Hohokam petroglyphs. Our leaders will be Hohokam scholars Paul and Suzanne Fish and Peter Boyle and Gayle Hartmann who led the AAHS rock art recording project on the hill. To register email Katherine Cerino. The trip is limited to 30 people.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Arizona Archaeological and Historical Society volunteers, University of Arizona students, and Pima College students excavated Whiptail Ruin, a village in the northeastern Tucson Basin that dates to the mid- to late A.D. 1200s. Analyses of the notes and artifacts from the site are now finished, with some interesting results.

Whiptail Ruin, situated in and around Agua Caliente Park and its hot springs, contains evidence that some of its residents were part of a thirteenth-century migration from the Mogollon highlands. Locally made corrugated pottery, Cibola White ware jars used as cremation urns, obsidian from the Mule Creek source near the Arizona-New Mexico border, and the use of tree-ring datable conifer wood in house building are indicators of strong ties with people outside of the Tucson Basin.

Other evidence suggests that Whiptail’s residents may have been specialized hunters. Skulls, jaws, horns, antlers, and lower leg bones of deer, pronghorn, and bighorn sheep appear to have been stored on shelves or on the roofs of houses. If the Hohokam were doing what historic O’odham hunters did, some of these items may have been parts of hunting costumes, while others were pieces stored away to protect the other villagers from the power of the animals that were killed.

In April’s talk, Linda Gregonis will discuss the possible role of hunting specialists and migrant families in the early Classic period as well as describing the challenges of working with data recovered and field notes made nearly 40 years ago by avocationalists and archaeological students.

Rock art is notoriously difficult to date and some dating techniques used for dating have been proven unreliable leading to considerable confusion in the literature on what is old and what is not. Using the best available dating of ancient rock art in western North America, I will discuss the present state of knowledge and present a visual perspective on the earliest styles and what they may tell us about the people who made them. Three significant styles or substyles are noted that date prior to the time of Christ. I will provide evidence for what people were doing at these early sites and consider who was making the designs and how often they were doing so. Included in the talk will be the first public presentation of data on a recently verified depiction of a mammoth and possible related Pleistocene megafauna.

- Members of the Snaketown ’65 crew

- Sarah Herr, Steve Lekson and Jenny Adams prepared to cut the cake

- Ray Thompson and the Kiva Doggerl

- ASM Director Beth Grindell pays tribute to Kiva

- Don Burgess at the Kiva Birthday Party

- Kiva reception

- Display of Hohokam Books at ASM Store

- 75 Years and counting…

- Kiva Editors

- Kiva Birthday Party

- Barneby Lewis from the Gila River Community

- Panel Session at Snaketown Symposium

- David Doyel

- AAHS President Don Burgess introducing David Doyel

- Henry Wallace, Bill Doelle and Steve Lekson – Snaketown Reception

- Snaketown Reception

- Snaketown Symposium Speakers, Patty Crown, Dave Wilcox and David Doyel

On March 5th and 6th, 2010 the Arizona Archaeological and Historical Society and the Arizona State Museum celebrated the 75th Anniversary of the excavations at Snaketown and the 75th Anniversary of it’s journal, Kiva.